The Father of Alaska Native Land Claims

By Joaqlin Estus (Lingít)

ince right now we’re really celebrating and looking at the 50th anniversary of ANCSA. I have to say that William Paul [Sr, Lingít] should be regarded as the father of Native land claims,” said Sealaska Heritage Institute President Rosita Worl, PhD (Lingít) after a recent talk on William’s early life by his grandson Ben Paul.

“We’ve had many, many great leaders who have come after him, but he was the one that began it,” she said.

Decades before Congress adopted the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA), the Lingít and Haida Indians of southeast Alaska waged claims battles launched by Paul (1885-1977).

Paul credited respected leader Peter Simpson (Tsimshian) for steering him in 1923 to take on land claims. He often told the story, which his son Fred repeated in his book, entitled Then Fight for It.

“Peter Simpson asked, ‘Willie, tell me one thing, ‘who owns this land?’

“William replied, ‘We do!’

“‘Then fight for it,’ Peter said with great firmness and authority in his voice,” Fred Paul wrote.

Civil rights and land claims became William Paul Sr’s life mission for more than 50 years.

Author and attorney Walter R. Echo-Hawk wanted to find out more about Paul during a visit to Alaska, he said in his book, In the Courts of the Conqueror: The Ten Worst Indian Law Cases Ever Decided.

“He became a charismatic orator with many accomplishments, supporters, enemies, victories, and defeats,” wrote Echo-Hawk.

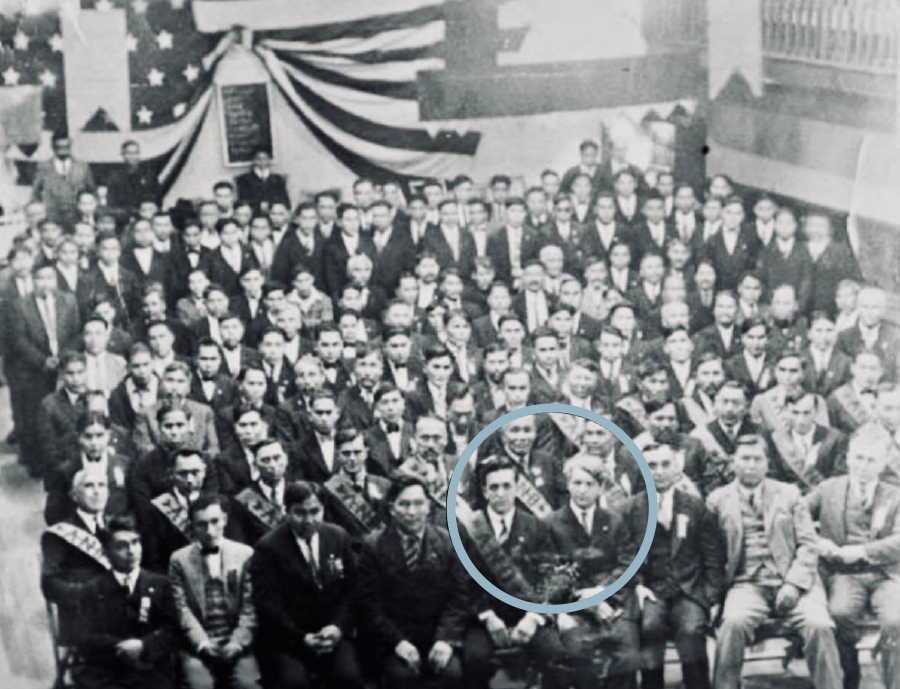

“During the 1920s, this Lingít lawyer emerged as a force. He attacked school segregation in Haa Aani (“our land” in Lingít), won citizenship for his people, secured the right to vote, and fought to protect salmon fishing. He helped build the ANB [the Alaska Native Brotherhood]—founded in 1912 as the nation’s first Native American civil rights organization—into a potent political voice,” Echo-Hawk said.

William replied, “We do!”

“Then fight for it,” Peter said.

The Alaska Native Brotherhood was formed just 7 years after the federal government took Native lands in southeast Alaska to create the Tongass National Forest. The brotherhood was primarily a southeast Alaska organization with some groups of members in other parts of the state.

“Paul’s feats are remarkable, because they were accomplished before the Indian Citizenship Act, at a time when Native Americans were a subjugated and demoralized race,” Echo-Hawk said.

The brotherhood took the first formal step to an Alaska Native claims settlement, Worl said.

District Judge James Wickersham had been instrumental in passage of laws that first made Alaska a territory then a state. In 1929 at the ANB annual convention in Haines, in Southeast Alaska, Paul and Wickersham urged delegates to adopt a resolution to pursue Native land claims.

“In 1935, the Lingít and Haida persuaded Congress to pass a statute that allowed them to pursue a seemingly improbable claim of aboriginal title to all of Southeast Alaska. They persevered in this quest for some 25 years,” said authors David S. Case and David A. Voluck in their book Alaska Natives and American Laws. The law authorized the Central Council of Lingít and Haida to sue rather than the brotherhood, which included non-Natives among its members.

“Their [the Central Council’s] victory, in 1959, just nine months after statehood, framed the arguments for all of the Indigenous peoples of Alaska and set the stage for the enactment of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, or ANCSA, in 1971,” Case and Voluck wrote.

Paul failed, however, in a 1955 lawsuit to persuade courts that the rightful owners of southeast Alaska lands were the traditional clans, not Congressionally created Tribes. Paul took the case all the way to the Supreme Court, which ruled against him.

Paul’s powers of persuasion, and aggressive style, more often brought him wins. “…anyone who knew William Paul understood that he wasn’t afraid of a fight,” said John Borbridge, Lingít, who lobbied for ANCSA. “He believed in the confrontational when it would serve the purpose,” Borbridge said in the film, “The Land is Ours.”

William and his brother Louis published two newspapers, the Voice of the Brotherhood and The Alaska Fisherman to spread word of ANB positions on issues, including William’s candidacy for the Territorial Legislature.

When Paul was elected in 1925, “the White political leadership went berserk over this. Here is an Indian moving in, playing by White rules, playing a White political game, and being in control.” said University of Alaska Historian Emeritus Steve Haycox, PhD, in the same film. “What are you going to do about that?”

White people spoke out against Paul in newspaper editorials. And he was disbarred in 1937 for taking payment out of a settlement rather than turning the settlement over to the client and requesting payment.

“Historians have commented, and I think correctly, that there are any number of members of the Anglo bar who could have been disbarred for the same sorts of things in that day and age,” Haycox said. “Why then did they go after William Paul? They went after William Paul because he had enemies, because his style was aggressive, and because he had power.”

As a teenager, Paul had gone to Carlisle Institute in Pennsylvania. Carlisle was run by Colonel Henry Pratt, of “Kill the Indian to save the man” notoriety. But Paul called him a hero, saying Pratt instilled in the students an attitude of, “you can do it.”

Worl said Paul took the best of what he was taught at Carlisle and made it work for Native people. “The fact that he learned how to run a printing press, that was probably one of the greatest things that he learned from Carlisle. So even though we in the contemporary period tend to really dismiss Carlisle or even talk about it in very negative ways, he was able to turn those things around.

“And I just wanted to say that I benefited directly from his teachings,” Worl said. “I became his student when I was 10 years old. And to me, he is a superhero.”

Others who said they learned a lot from Paul include Etok, or Charles Edwardson, Jr (Inupiaq), who testified before Congress; and Don Wright, Athabascan, who also testified, and who met with President Nixon on ANCSA.

In October 1971, two months before ANCSA was adopted by Congress, the Alaska Federation of Natives voted on a resolution to approve the bill’s adoption.

Paul spoke against the measure, saying it gave title to too little of the land Natives owned under aboriginal title. ANCSA transferred title to 44 million acres to Native for-profit corporations — just 12 percent of Alaska’s 375 million acres. By comparison, the largest Lower 48 reservation is the Navajo Nation at 17,544 million acres.

Paul said ANCSA also didn’t protect Native subsistence hunting and fishing rights. To this day, subsistence remains as one of the key unresolved issues of Native claims that cause controversy.