Mountains and Wind and Lost Souls

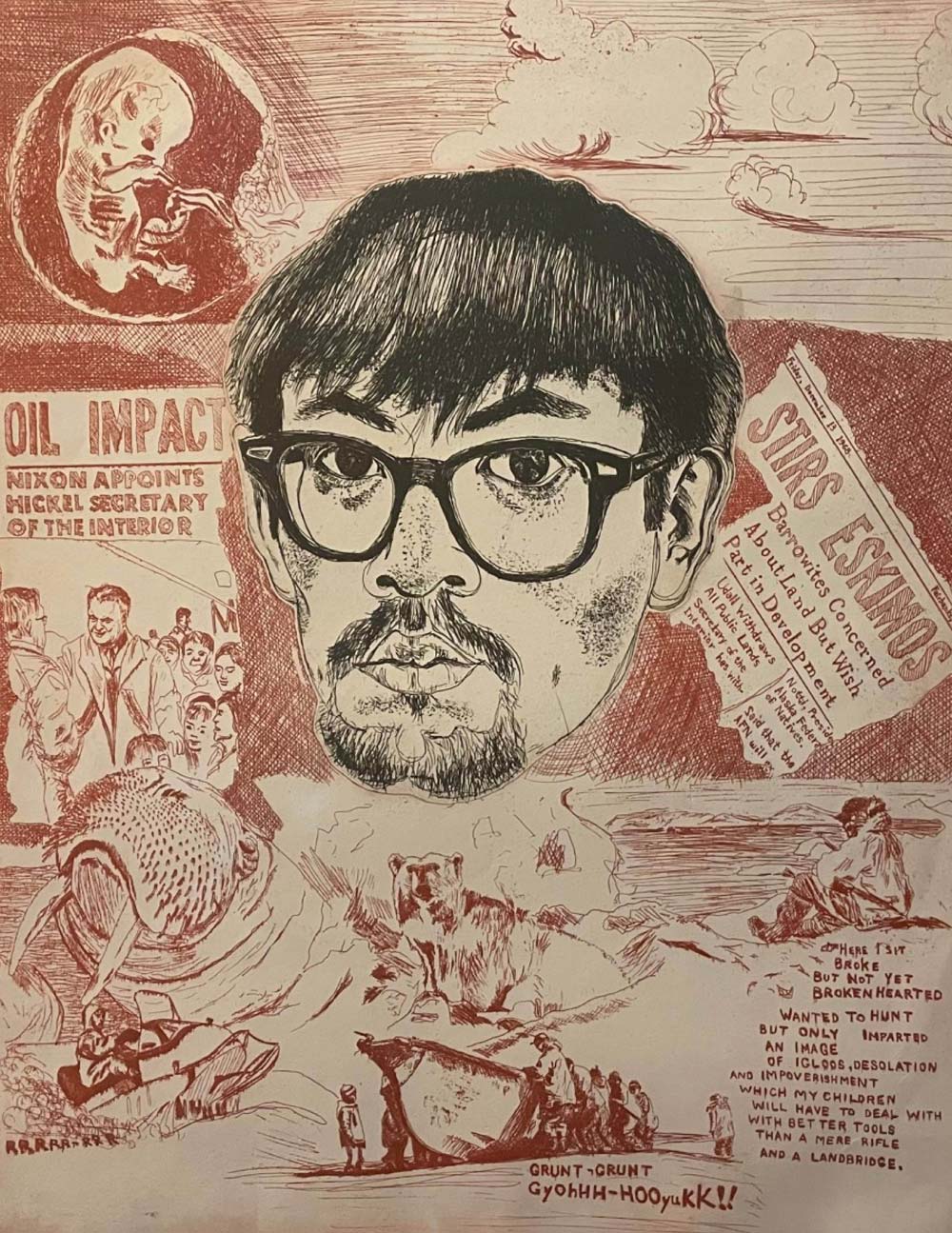

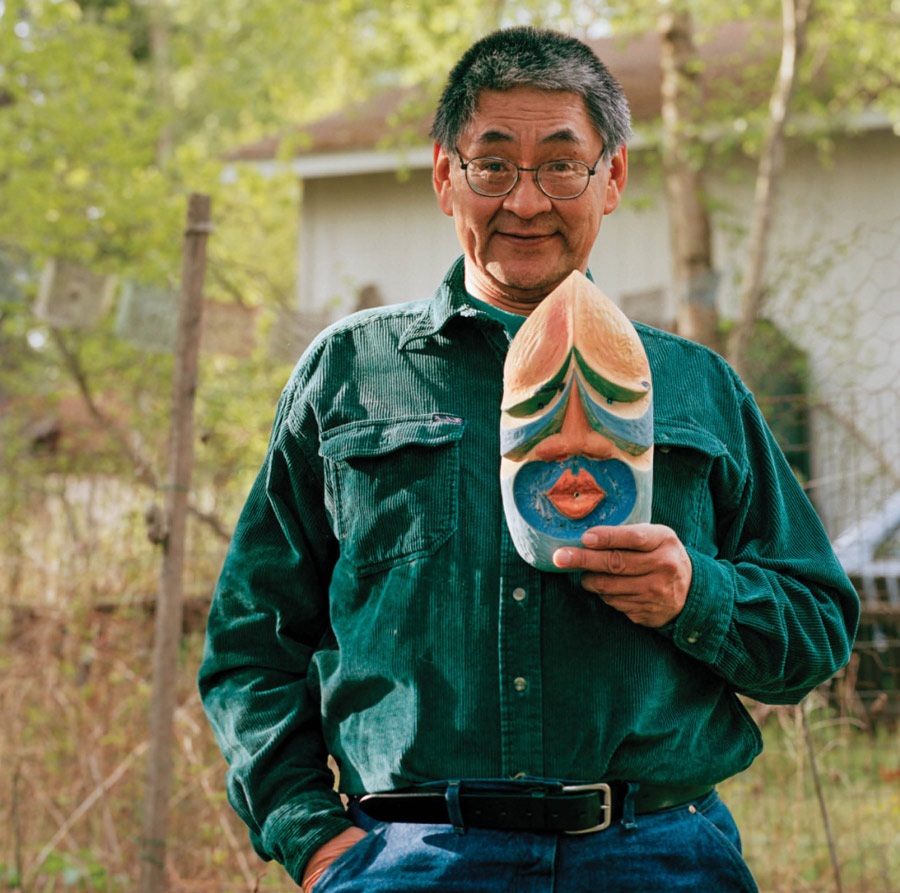

oseph Engasongwok Senungetuk, Iñupiaq, died peacefully on May 31 at his home in Anchorage, Alaska with his wife Martha and family and friends by his side. He was 83.

As an artist, he created etchings, paintings, illustrations, masks, sculptures and writing. He will also be remembered as an educator, mentor, and activist.

Senungetuk said the inspiration for his art work came from museum illustrations and objects. “Most of my ideas come from pre-contact days. In my art work I try to show people that we are an ancient people and we go back thousands of years,” he said in the documentary film, “Joe Senungetuk, Art and Life” by Mike Conti.

He used those traditional designs in a contemporary fashion, said Victoria Hykes-Steere, Iñupiaq, assistant professor of Alaska Native governance, Alaska Pacific University. She said a recurring theme was the impact of colonization.

courtesy of Martha Senungetuk

courtesy of Martha Senungetuk

Mountains and Wind and Lost Souls

oseph Engasongwok Senungetuk, Iñupiaq, died peacefully on May 31 at his home in Anchorage, Alaska with his wife Martha and family and friends by his side. He was 83.

As an artist, he created etchings, paintings, illustrations, masks, sculptures and writing. He will also be remembered as an educator, mentor, and activist.

Senungetuk said the inspiration for his art work came from museum illustrations and objects. “Most of my ideas come from pre-contact days. In my art work I try to show people that we are an ancient people and we go back thousands of years,” he said in the documentary film, “Joe Senungetuk, Art and Life” by Mike Conti.

He used those traditional designs in a contemporary fashion, said Victoria Hykes-Steere, Iñupiaq, assistant professor of Alaska Native governance, Alaska Pacific University. She said a recurring theme was the impact of colonization.

“His art expressed that conflict between Western and Iñupiaq worldview, about who we are and how we carry ourselves and how we live and we die,” Hykes-Steere said.

She said his work brought out the dignity and honor of older generations as well. “Joe loved the beauty of our world. So he didn’t just talk about colonization. He also showed in his work the beauty of being human.”

Joe and his wife and fellow artist Martha Senungetuk were Elders/Artists in residence at Alaska Pacific University. Hykes-Steere praised their role there, “I am so grateful for him and Martha for being a light on campus for Native and non-Native students. Students loved having them in the Art Studio and on campus. They were everyone’s grandparents or Elders and so many students credited their presence there with their graduating.”

Wilson Justin, Ahtna Athabascan, cultural ambassador, Cheesh’na Traditional Council, said in an email, “more than anything else I remember Joe as an oasis in the desert. He gave comfort to lone travelers and lesser known voyagers. As an artist he knew mountains and wind and lost souls.”

Photographer Bill Hess got to know Senungetuk through a project to photograph Alaska Native U.S. military veterans. Hess said in an email that Joe told him about befriending a 10-year-old orphaned boy while stationed in Korea. “He talked to the boy, he listened to the boy, he made friends with the boy…Perhaps this (friendship) was in part because Joe knew what it was like to have people from other places come into his homeland and assume control.”

As a youth she first read Joe’s groundbreaking book, Give or Take a Century: An Eskimo Chronicle, and remembers “the singularity of Joe’s voice, its veracity, its elegance and intellect. But his writing also gave me a true account of what my family’s life was like in Nome after leaving King Island,” she said in an email.

“As a child myself, what a gift it was to hold a book in my hands that supported these true stories [that Kane’s mother had shared with her], that made them more vivid because of the brilliance and veracity of the writing,” Kane said.

She quoted a passage by Senungetuk: “We laughed together, my friend Pete [Seeganna] and I, at the ludicrous vision conjured up by his tale of the polar bear hunt. But sadness lay within the laughter. The uninhibited friendships of the people, whether hunting or relaxing, in fun or sorrow, will be difficult to recapture.”

“Of all the men who once carved with my grandfather in Nome in the 1950s and 1960s, Joe was the one to put carving tools in the hands of my children and impart to them the knowledge, said and unsaid, that they would need…” Kane said, “Joe gave generously of his love, knowledge, genius, humor, and hope.”

She said Senungetuk once joined her via Zoom, “where he was a welcome presence during a Cambridge (Massachusetts) Public Library reading of a book I never would have written without Joe’s visionary legacy of art, Joe’s complex and formidable literary work, Joe’s leadership, Joe’s friendship, Joe’s love, Joe’s encouragement, and Joe’s unwavering support. To Joe’s memory and Joe’s Iñua (spirit), I give thanks now and for all of time. May those of us who remain here honor and celebrate the life of a true original,” Kane said.

Senungetuk graduated from Nome High School in 1959 and studied for two years at the University of Alaska Fairbanks before serving a year in South Korea as an Army radio teletype operator and six months at Ft. Richardson near Anchorage.

In 1965 he entered the workshop at Sitka’s National Park Service Visitors Center as an Artist in Residence.

He enrolled as a student of the San Francisco Art Institute and worked at the Indian Historian Press, which published his book, Give or Take a Century: An Eskimo Chronicle.

He then traveled extensively to Alaska villages in the Village Art, and Intercultural Coordination programs at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

He worked for two years at Sitka’s Sheldon Jackson Junior College as an instructor in Native art and history. He became an artist in residence in 1976 at the art cooperative Visual Arts Center of Alaska in Anchorage before becoming an independent artist.

In addition to his autobiography, he was a columnist for the Anchorage Daily News from 1989 to 1994.

Senungetuk helped shape policy as a board member for numerous organizations such as the Visual Arts Center for Alaska, Institute of Alaska Native Art, Anchorage Museum Association and the University of Alaska Chancellor’s Select Task Force on Native Higher Education.

Joseph Senungetuk died from complications of Parkinson’s disease.

He is survived by his wife and fellow artist Martha Senungetuk; son, William Guugzhug Senungetuk, daughter Jenny Senungetuk and grandchildren Violet, Silas, and Hazel Kuner; step-daughter Aurora Buchwald and her children Tyler, Gianna and Cyrus; sister Cora Olsen; and extended Senungetuk family. He was preceded in death by his parents Willie and Helen Senungetuk, siblings Nancy, Ron, and Stanley Senungetuk, and wife Catherine.